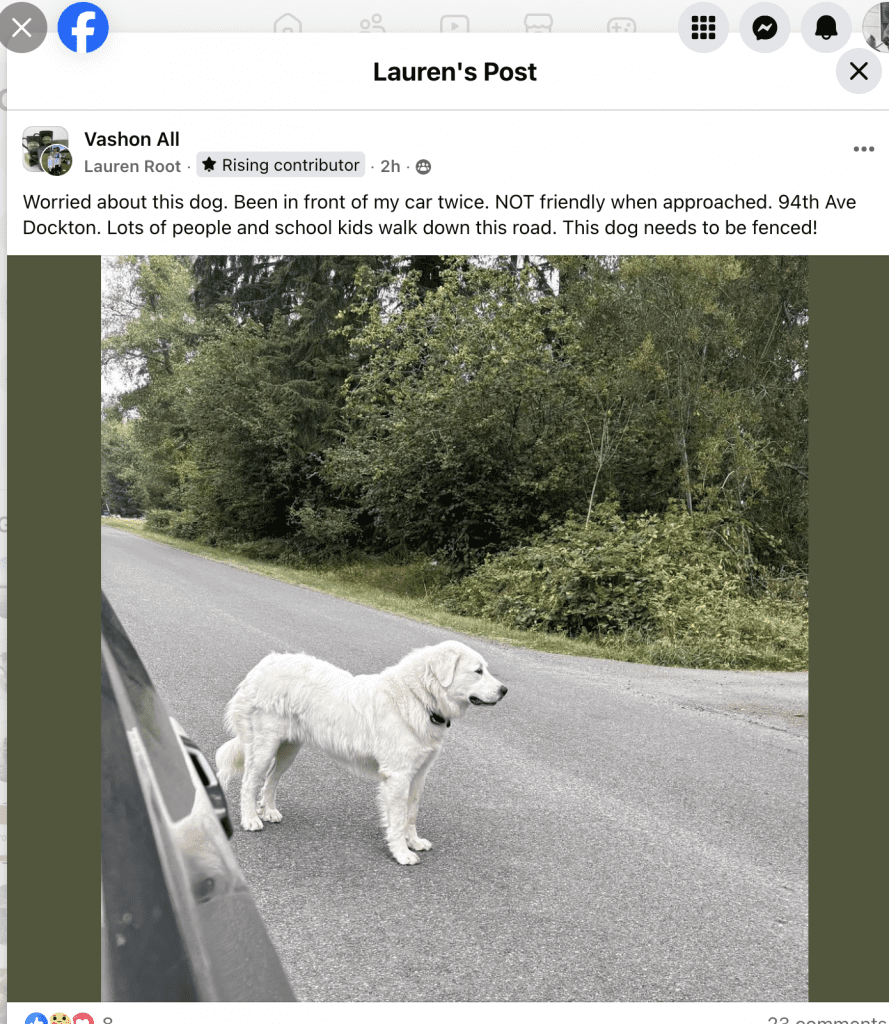

The other day, I saw a post making the rounds online with a photo and a warning:

“Worried about this dog. Been in front of my car twice. NOT friendly when approached. 94th Ave Dockton. Lots of people and school kids walk down this road. This dog needs to be fenced!”

The comments section lit up quickly, many mentioning Great Pyrenees and their reputation as livestock guardians. Some people were supportive, others were critical, and a few admitted they didn’t understand what these dogs are bred to do.

I’d like to offer some thoughts, because this is an issue that touches the heart of living on Vashon.

Livestock guardian dogs (LGDs), like the Great Pyrenees, Maremmas, and Anatolian Shepherds, aren’t backyard pets. They are bred and trained to patrol, watch, and protect animals from predators. On an island where people raise horses, goats, chickens, and sheep, these dogs play an essential role. Their job is not to wag their tails at strangers. Their job is to bark, stand their ground, and make coyotes or raccoons think twice about coming too close.

So, when someone encounters one on the road, it can feel quite unsafe. However, often what appears to be aggression is actually the dog doing what it was bred to do: protect.

The criticism that “these dogs need to be fenced” is valid to some extent. Fencing is essential, and most farm owners do everything they can to keep their dogs where they belong. However, on a 10-acre or more property, fencing every corner with deer-proof barriers can be expensive and sometimes unrealistic. Many farms use a combination of traditional fencing and invisible fencing, and even then, determined guardians will sometimes test their boundaries.

It doesn’t mean the owners don’t care. It doesn’t mean the dog is neglected. It means we live in a rural area, where working animals perform traditional rural tasks.

When I think about these debates, I remember my grandparents’ farm in southern Indiana in the 1960s. Back then, every farm had dogs. They weren’t house dogs or pets who stayed inside — they were barn companions, shadows in the pasture, and faithful watchers of the night. I can still picture one of them stretched out under the maple tree by the porch, ears pricked to the sound of cattle lowing in the distance, or loping along the fence line with the morning fog rising off the fields.

Nobody thought twice if a dog wandered down the road, because everyone understood their purpose. They were as much a part of the farm as the chickens scratching in the yard or the horses shifting in the barn. Life was rougher around the edges then, but there was a rhythm, a balance, between people, animals, and land. Neighbors didn’t jump to conclusions — they trusted each other, and the dogs, to play their roles.

That memory sticks with me, because it shows that these conversations aren’t new. The role of guardian dogs has always been misunderstood by those who haven’t lived alongside them.

Neighbor to Neighbor

What concerned me most about the post wasn’t the dog, but the way the frustration was broadcast online before the farm owner was contacted. What did that accomplish besides stirring fear? On this island, being a good neighbor means reaching out directly. Knock on a door, leave a note, or send a message. I’ve seen more problems solved that way than through public shaming.

A Community Balance

I understand the perspective of parents whose kids walk down Dockton Road and feel uneasy seeing a big white dog. That’s real. But I also understand the farm owner whose dog is guarding fillies, goats, chickens, and even barn cats. Both realities can exist at once.

My hope is that we approach these situations with compassion and understanding. Livestock guardians will sometimes get out, just as horses sometimes break fences or chickens sometimes end up in the neighbor’s yard. Instead of escalating online, let’s talk to each other.

That, to me, is what island living is supposed to be about.

If You Meet a Guardian Dog

Guardian dogs may look imposing, but they are storytellers of the land itself — carrying centuries of instinct in the way they stand, watch, and bark. If you encounter one, here are a few things to keep in mind:

- Stay calm, like you would with a deer in the woods. These dogs read energy, and they respect steadiness.

- Give them space to do their work. They’re not strays looking for scraps. They are keepers of flocks and fields.

- Resist the urge to reach out. Their loyalty belongs to the animals they guard, not to passersby.

- Use your voice, not your fear. A firm, steady “go home” carries more weight than you’d think.

- Remember their story. They are here because farms, with their horses, pigs, sheep, goats, and chickens, need them. They are threads in the larger fabric of island life.

If ever you feel uneasy, the best thing you can do is talk to the farmer. Neighbor-to-neighbor, we can keep both kids and animals safe while respecting the work these dogs have been bred for generations to do.