Being just short of her thirtieth birthday, Henrietta Hemlock was too young to die. Her knowing neighbors nodded their heads sagely and said, “spongy root rot,” or “blight” or “hemlock looper.” The more pretentious among us said, “Rhizocotonia Butinii” or “Lambodina Fiscellaria,” which are just fancy names for the same things everybody else was saying.

The death might have rested with a diagnosis of natural causes of unknown origin had an autopsy not been performed. The arborist found no signs of webbed leaves, loopers, or rotted roots. Thus, the official conclusion of the query into Henrietta’s death became, “I don’t know. All the other trees look okay.” And there the matter sat for months. Absolutely nobody suspected foul play. After all, she didn’t have any chainsaw wounds or suspicious holes. Even the local gardener didn’t suspect the truth, but the truth came out.

The first breakthrough in the case came when I was looking for a place to plant a eucalyptus. I found the perfect spot on the edge of the woods. The tree would get enough sunlight there. I’d planted a eucalyptus once before in my other sunny spot, but it tragically died along with an acacia planted nearby. My Perfect Sunny Spot already had a wire cage around it where I’d planted a juniper. The juniper had died. I shook my head over my sad luck with my trees and shrubs.

To prepare to plant my eucalyptus, I took a course on transplanting, taught by Linda Chalker-Scott, a PhD in agriculture. She works at the WSU extension station in Puyallup. I studiously watched how she aggressively prepared the root ball. Was that my problem? I wasn’t opening up the center of the root ball, leaving the poor plants rootbound. As I watched the demonstration, I remembered her research on wood chips and her nattering on about how conifer wood chips aren’t toxic. I dismissed the thought with a, Who Cares? However, she knew something I didn’t.

At the end of the class on transplanting, I thought about my method of transplanting. You know, I think I really was opening the root ball enough. I was being careful to break up the layer of clay under the topsoil. I never did anything as crass as digging a hole with a backhoe. I don’t even own a backhoe. Still, I had a long list of trees and shrubs representing thousands of dollars in expenses that had died in my yard.

The first eucalyptus and its companion acacia had made such a charming blue and yellow vignette on the edge of the forest. I still grieve for them. The Alaskan yellow cedar was another hope for a bright spot at the edge of the forest. I’d imagined it shining like the rising sun along my east border. Wait, the eucalyptus, acacia, and Alaskan yellow cedar all came in bare roots. They weren’t rootbound. I’d nurtured and pampered those baby trees, and they thrived for the first five years. They were starting to look impressive in their sixth year when they suddenly died. I looked at the snag of poor Henrietta Hemlock and a chill ran down my spine. Was it possible that we had a serial killer on the loose on Vashon? Was it me?

Before condemning another expensive plant to an untimely death, I did some more reading, focusing on plants that are allelopathic; those that exude poisons through their roots. Aha, Douglas fir was listed among the several allelopathic trees. This was why the WSU researcher had spent so much time researching wood chips from fir. I’d found my serial killer. All the shrubs that had died in my yard were planted just outside the drip line of the first. I did more reading. Prominent permaculture writers Sepp Holzer and Paul Wheaton are quick to give the Doug Fir a bad rap, calling them weeds producing a fir desert. Wheaton dismisses the claim that Douglas firs are native by comparing the thousand-year life span of trees to the eighty years of a human, suggesting that it’s presumptuous for such a short-lived creature to decide what is native. He asks, “native to when?” Perhaps the Doug Fir is just a toxic invasive species in the world of long-lived trees.

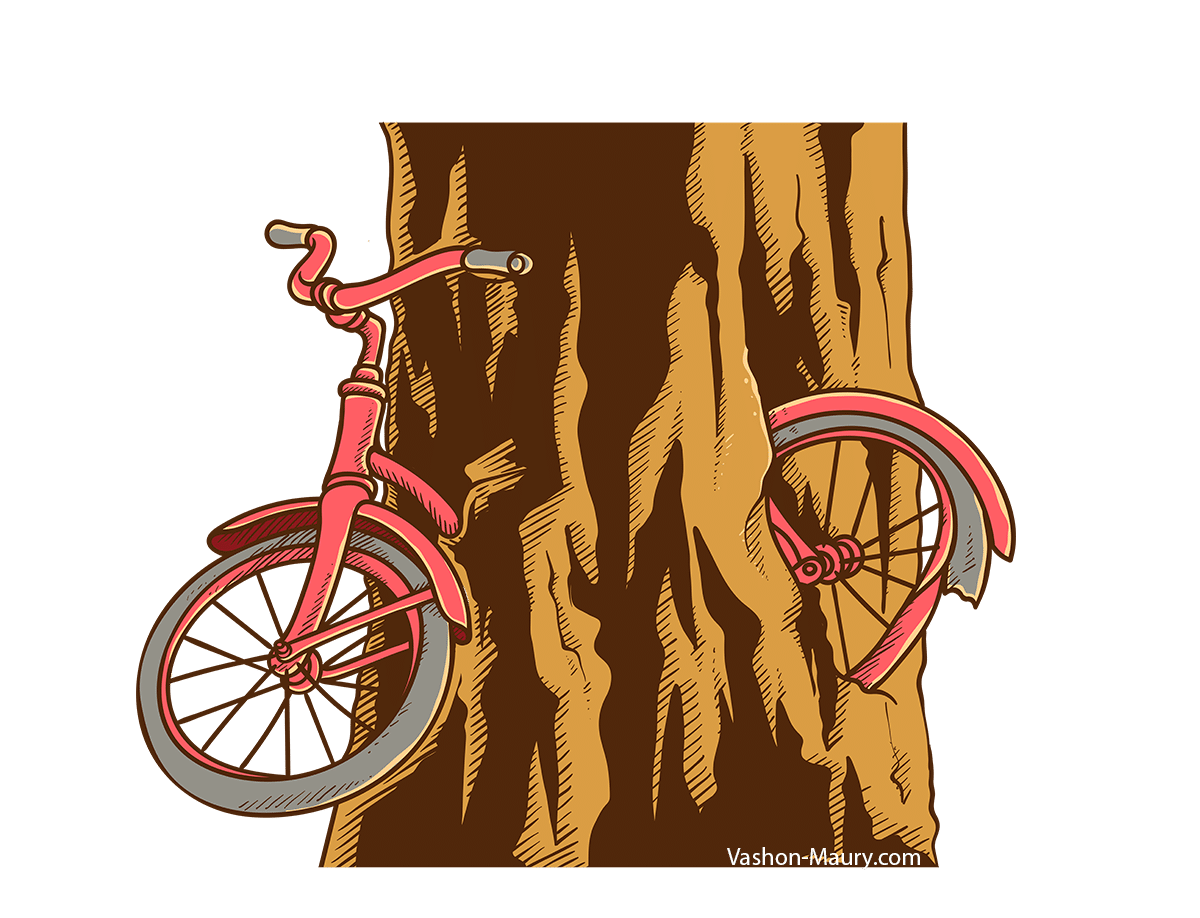

To further support my theory, I looked at Henrietta Hemlock’s history. She sprouted in a grass field at the edge of a logging road. Her neighbors were a dogwood and a couple of madrone. She had some shade from big firs downhill, but their roots were far from hers. About ten years ago, hundreds of baby Doug Fir sprang up. They flourished until they completely surrounded the thriving hemlock. Had the younger trees attacked and killed her? The evidence would indicate so.

Satisfied with my conclusion, I plotted out where I could plant my eucalyptus so it would be safe from the toxic firs. Fortunately, I also kept reading. In her book, Finding The Mother Tree, Suzanne Simard tells us the roots of trees are covered in mycorrhiza, which gets food from fungi that transport water and nutrients from the soil to the trees and from mother trees to their offspring. The fungi feed the trees and produce edible chanterelles and morels and not-so-edible mushrooms, Pseudomonas Fluorescent (PF). The PF grows on the roots of broad-leaved deciduous trees like birch and is beneficial in fighting pathogens that can harm the trees. It’s the trees’ best defense against Armillaria Ostoyae, a fungus that has been known to kill whole forests of conifers.

Glancing at the dead snag that is all that remains of Henrietta, I don’t see any deciduous trees that would host PF. While the Doug Fir are numerous enough that they might be able to share enough antibiotics to defend against Armillaria ostoyae, Henrietta was alone. She had no ancient mother tree to come to her defense. I now have to ask. Was Doug Fir framed? Is the fungi Armillaria ostoyae the natural serial killer? We may never know, and I may never find a safe place to plant my eucalyptus.

Excellent cautionary tale!